The High Cost of Data Centers in America (and Who Actually Pays It)

Data centers are the physical underside of the internet. They are also quickly becoming the physical underside of the AI boom.

And in America, we’re learning a familiar lesson: when something becomes critical infrastructure, the costs have a weird tendency to socialize, while the profits stay private.

If you’ve been following the headlines, you’ve probably seen the two extreme narratives:

- Data centers are pure economic development, a tax base miracle for struggling towns.

- Data centers are pure extraction, a new kind of resource mining that drinks power and water and leaves little behind.

Reality is trapped between those.

Some communities have absolutely used data centers to fund real improvements. The Iowa Public Radio reporting on rural data center towns captures that tension well, because locals can see both the money and the trade-offs in the same week.

But if you want to understand the high cost of data centers in America, you have to zoom out from the building itself.

The big cost is not “servers are expensive.” The big cost is everything around the servers.

TL;DR:

- The hidden bill - Power delivery, transmission, substations, backup generation, water, land, and public services

- The jobs math - Huge construction surges, then relatively small permanent staffing

- Incentives and risk - Tax breaks can turn “growth” into a public-funded discount

- Water is a real constraint - Cooling demand meets drought politics and local supply limits

- Grid upgrades pick winners - Who pays for new lines and substations is the whole fight

- A better deal - Requirements that keep benefits public and costs priced in

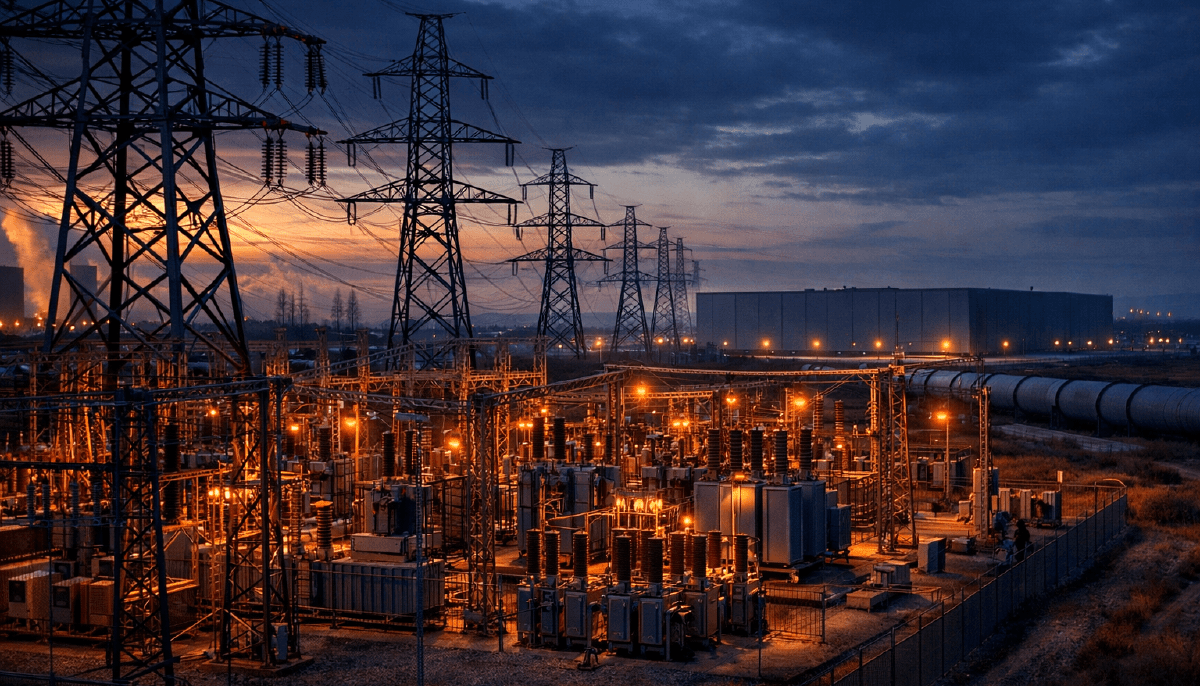

The Hidden Bill Is Everything Around the Building

A data center looks like a warehouse with expensive guts.

The public costs come from the fact that it is not really a warehouse. It is an industrial-scale power-and-cooling plant that runs 24/7 and expects near-perfect uptime.

That means the “project” often includes:

- New transmission and distribution capacity (sometimes entirely new substations)

- Upgraded feeders and interconnection work

- Massive backup power (generators, fuel logistics, emissions permits)

- Water system expansion or rework (or expensive alternatives like reclaimed water)

- Road upgrades and construction impacts

- New public safety and planning load (permitting, fire, emergency response)

Some of that is paid by the developer. Some of that is paid by utilities. Some of that is paid by local government.

And some of that lands on everyone else because the financing mechanism is designed that way.

Checkpoint question: When you hear “$X billion investment,” do you know how much is private capital, and how much is public infrastructure spending disguised as “development”?

The Jobs Math Is Not What People Assume

This is where a lot of communities get emotionally whiplashed.

During construction, data centers can create a very real boom. The rural Louisiana example is dramatic: Meta’s planned AI complex was described as a $10B investment with expectations of thousands of construction workers at peak (Grow NELA’s announcement materials and the broader reporting around the project echo this scale).

This is why small towns get excited. Construction brings:

- Hotels actually booked on weekdays

- Restaurants with a line

- Overtime pay for trades

- A sense that something is happening

Then the build ends.

Operational staffing is typically much smaller. The rural reporting and summaries of industry patterns often put long-term staffing per building in the dozens, not the thousands.

This is not a moral failure, it’s the nature of the asset. A modern data center is capital-intensive, automation-heavy, and security-controlled. It’s designed to run quietly.

So if the entire political sales pitch is “jobs,” you’re likely to end up disappointed, even if the project technically “delivers.”

That’s also why the Phoenix city manager quote hits so hard in the rural data center literature: a data center can take a lot of land without providing enough jobs to justify major infrastructure investment. (This quote appears in the rural community synthesis that pulls from Western reporting.)

Tax Revenue Can Be Real, Which Is Why This Gets Confusing

There’s a reason local officials sign up for these deals.

In some places, the tax story is genuinely wild.

The rural data center synthesis points out examples like Loudoun County, Virginia (often branded the “data center capital”), with data center tax revenue reaching an estimated $890 million annually. In Quincy, Washington, data center campuses have been reported as paying the majority of city property taxes, funding public amenities that would have been impossible otherwise.

That’s not nothing. In a lot of rural America, it’s basically a cheat code.

But here’s the part that matters for “high cost” framing:

- That tax windfall is not guaranteed everywhere.

- It can be eroded by incentives.

- It can be offset by utility and water costs that don’t show up in the same budget line.

In other words, a data center can be a fiscal miracle in one county, and a lopsided deal in the next county, even if the buildings look identical.

The Subsidy Trap: When Incentives Turn Into a Bad Deal

The ProPublica reporting on Washington’s data center tax break is the canonical example of the question communities should be asking: If the state is giving up revenue to attract the project, what exactly is the public getting back?

Incentives can include:

- Property tax abatements

- Sales tax exemptions on equipment

- Special utility rates or infrastructure arrangements

- Fast-tracked permitting and zoning concessions

These are often sold as “we have to compete.”

And sometimes, yeah, there is competition.

But the competition dynamic is also how you get a race to the bottom, where every town offers just a little more until the deal stops looking like an economic development plan and starts looking like a corporate discount.

The quiet risk is that communities lock in long-term concessions for an asset that may not employ many locals long-term, may not buy much locally after construction, and may put long-lived strain on utilities.

If you want a practical, non-ideological rule: don’t subsidize what would have come anyway.

That sounds obvious. It is not how these deals are usually structured.

Water Is Quietly Becoming a Deal Breaker

The Environmental and Energy Study Institute’s overview of data center water consumption is worth reading if you want to understand why this is turning into local political warfare.

A lot of people still picture “the cloud” as weightless. Water issues are the reality check.

Data centers create heat. Heat must be moved. Sometimes that’s done with air. Sometimes it’s done with water. Sometimes it’s a hybrid. The details vary, but the conflict looks familiar:

- Towns with limited water supplies see data centers as a new industrial demand category.

- Residents ask why their watering restrictions exist if a corporate facility can expand usage.

- Officials get squeezed between economic development promises and resource constraints.

Western reporting summarized by Stanford’s “& the West” project emphasizes how AI-era growth is colliding with power and water limits across the region.

This is not a “green vs growth” argument. It’s physics.

If a community’s water system is already tight, a deal that depends on water expansion is not a tech deal, it’s a water deal.

Power Upgrades Pick Winners, and Ratepayers Notice

This is the core of the “high cost” story.

Data centers don’t just buy electricity like a normal business. They can become one of the largest loads on a utility system. That can force:

- New substations

- New transmission capacity

- More generation procurement

- Rebuilt distribution infrastructure

When a giant load shows up, somebody pays for the upgrades.

There are a few ways this is handled in practice:

- The developer funds a big share directly (best case).

- The utility funds it and spreads costs across ratepayers (common fight).

- A hybrid model with cost sharing that is politically negotiated.

If you’re a resident or a small business, the question is simple: Are my rates going up to subsidize a private facility’s interconnection?

If you’re a local government, the question is: Will the tax base gains exceed the infrastructure and public service costs, including the ones that don’t hit my budget directly?

The Washington Post interactive analysis on “supersized” data centers frames the scale shift bluntly. These projects are getting bigger, which means grid impacts get bigger, and grid negotiations get uglier.

And once you’ve built the infrastructure, you’ve effectively committed the region to being a data center region.

That’s not inherently bad. It just needs to be an explicit choice, not an accidental one.

Local Democracy Problems: NDAs, Speed, and “Oops, It’s Already Approved”

One of the most under-discussed costs is governance.

The rural reporting includes multiple examples where:

- Deals move fast

- Details stay vague

- Officials sign NDAs

- Residents learn about it late

The Taylor, Texas case (covered via Straight Arrow News and echoed elsewhere) is a good illustration of how quickly “economic development” can turn into a legitimacy crisis when people feel a major land-use decision was made in secret.

Even if the project is “legal,” the process can still poison the relationship between residents and local government.

And when the next project arrives, the trust is already burned.

So Are Data Centers Good or Bad?

Both answers are too easy.

Here’s the most honest assessment I can offer:

- Data centers are real infrastructure. We need them.

- AI is making the scale problem worse. It’s not just more of the same.

- The costs are not imaginary. They show up as water fights, grid fights, land fights, and political fights.

- The benefits are not imaginary either. Tax revenue can be massive in the right structure.

The policy failure is treating them like any other “business attraction” project.

A factory that employs 800 people and runs two shifts is a different civic bargain than a facility that employs 40 people but demands the electric footprint of a small city.

America is still catching up to that distinction.

What a Better Deal Looks Like

If local governments want to avoid getting steamrolled, the “better deal” playbook looks pretty consistent across the places that have learned the hard way:

- Require infrastructure cost participation (substations, feeders, grid upgrades) instead of pushing it onto ratepayers.

- Water transparency requirements (reporting, caps, seasonal constraints, and reclaimed-water mandates where feasible).

- Real community benefit agreements that are more than a one-time donation, including funding for local job training and emergency services.

- Sunset clauses on incentives so towns can re-evaluate after the initial hype period.

- Zoning and planning that treats data centers like industrial infrastructure, not like “quiet commercial.”

- Regional coordination so towns don’t undercut each other in a race for the same project.

Some counties have gone as far as moratoria to buy time and set rules (Iowa’s Johnson County debate is a current example).

That’s not anti-business. That’s a community realizing it’s negotiating with one of the most powerful industries in the country.

Bottom Line

The high cost of data centers in America is not the cost of computing.

It’s the cost of turning electricity, water, land, and local governance into inputs for a machine that mostly serves people somewhere else.

And that’s the part we can actually negotiate.

If we want data centers to be a net public good, the deal has to be built like a public good deal. Transparent. Priced honestly. Structured so the community isn’t left holding the bag.

Because otherwise we’re going to keep repeating the same pattern: build fast, subsidize quietly, fight later.

Sources used while drafting (from the provided PDF’s source list)

- Iowa Public Radio: AI is driving a data center boom in rural America

- ProPublica: A Tax Break for Washington Data Centers Promised Jobs. Is It Paying Off?

- Stanford “& the West”: Thirsty for power and water, AI-crunching data centers sprout across the West

- EESI: Data Centers and Water Consumption

- Washington Post: Supersized data centers are coming. See how they will transform America.

- CBS2 Iowa: Johnson County imposes moratorium on data centers